R.B. Kitaj

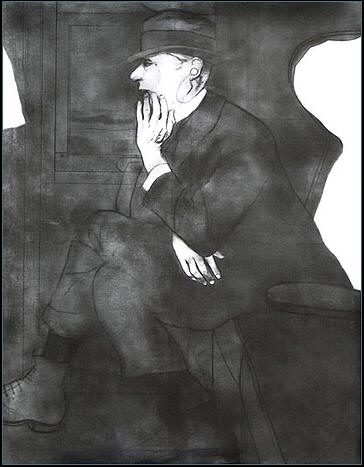

"The Jew, Etc. is the first picture that is about Kitaj's fictive figure Joe Singer. He is Kitaj's metaphor for the survivors of the Shoah. The historical event is turned into a current issue. The traumatic experiences are transferred into the present. The picture of the Jew in a train compartment visualizes the physical and mental restriction of the Diaspora. The crampedness of the compartment is passed on to the introverted person in the picture. The hearing aid stresses the isolation. Being on the move, in this case traveling on a train, is in Kitaj's sign system a symbol for the state of restlessness Jews were in. The picture of the wandering Jew who is driven from one place to another. The only safe place to escape to is the world of thoughts."

url-source: www.geocities.com/pantherprousa/bacon/kitaj_bacon.html

url-source: www.geocities.com/pantherprousa/bacon/kitaj_bacon02.html

"THE JEW, ETC."

1976-79

oil and charcoal on canvas, 152.4 x 122 cm

The Jew, Etc. 1976

I have long since resolved to be a Jew . . . I regard that as more important than my art. SCHONBERG

"I've seen people wince at this title; sophisticated art people, who think it's better not to use the word Jew. Kafka, my greatest Jewish artist, never utters the word once in his work, so I thought I would. This name-sickness, which many Jews will recognize and understand in different ways, is so touching to me, that I've also given my Jew a secret name: Joe Singer. Now it's not secret anymore.

In this picture, I intend Joe, my emblematic Jew, to be the unfinished subject of an aesthetic of entrapment and escape, an endless, tainted Galut-Passage, wherein he acts out his own unfinish. All painters are familiar with the forces of destiny embedded in happy accident and other revelations and failures which inform one's painting days. In that way, I'd like to expose Joe, in his representation here, to a painted fate not unlike the unpredictable case of one's own dispersion in the everyday world. For instance, before long I may name Joe's fellow passengers, those you can't see unless I paint them in; even though there's not much room left. In fact, I've begun to people this train-compartment in my journal. One of Joe Singer's jobs relates to a tradition of our exile, which influences this picture, whereby living messengers are trained up, who takes the place of books, in order to preserve a freshness of teaching, not endangered by date or dogma. Joe is the messenger-invention of my own peculiar dispersion (Galut), about which I learn more every day. His depiction on his expiatory pilgrimage, presides over what belongs to my sense of that changeful exilic condition and its uncertain art habits and futures, as in these beautiful lines about the Jews by the Catholic Pé: 'Being everywhere, the great vice of this race, the great secret virtue, the great vocation of this people,'"

R.B. KITAJ

Prefaces by R.R. Kitaj, R. B. Kataj, by Marco Liningstone, Thames and

Hudson, 1992

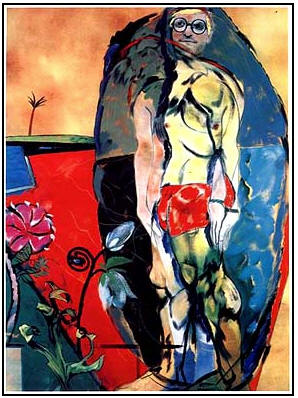

David - the Neo-cubist

| "THE NEO-CUBIST," 1976-87 oil on canvas, 70" x 52" The Saatchi Collection, London |

"DAVID," (unfinished), 1976-77 oil & charcoal on canvas, 72" x 60" |

". . . I began the portrait of Hockney in the 'seventies. I didn't care much for it, and it lay in storage for many years. In the later 'eighties, David described to me the death of his friend Isherwood in California. I took up the old portrait again and drew a kind of alter-figure across the original full-frontal one, with Chris Isherwood in mind. Like Hockney, and unlike me, he had been a very optimistic and sublime personality, so I made of them a sort of Cubist doppelganger, representing both life and death in the particular, widely perspectival California setting they made their own in exile and, I hope, in some harmony with David's recent neo-Cubist theory for pictures."

from R.B. Kitaj's statement in: Exhibition Road, 1988

"The Neo-Cubist is Kitaj's most astute comment on the state of painting today. It pokes gentle fun at artists' aspirations to follow on where the Cubists left off, but also it shows how painting has evolved in the last seventy-five years. Between 1976 and 1987 Hockney, a close friend ever since their first year at the Royal College together, has been experimenting with photo-montages and prints. These works have been heralded by some as the natural successors to the great Cubist masterpieces. Kitaj as been doing the same in oils. In The Neo-Cubist Hockney is dislocated in a Cubist manner to reveal more sides than normally possible on a two-dimensional surface, but the painting is not restricted by the rules of Cubism. It shows Hockney stepping out from a mammoth egg shape. He floats in a landscape rich with references to Matisse, other Kitaj works, and his own Splash paintings.

Kitaj as usual is best at describing his own imagery. 'The "egg" shape,' he writes, 'is my mimicry of that grey Cubist ellipse which sometimes frames classical analytic Cubist compositions. I meant the lush plant life to stand for the artificial garden paradise one finds in Los Angeles, and in Hockney's own garden there. I began the painting as a nude (of D. H.) about twelve years ago. It had been in storage all these years - then a year or so ago, when his dear friend Isherwood died and Hockney related his last days and hours to me, I got the old failed painting out in order to transform it, with Isherwood's ghost dislocating (as you say) Hockney's form, after his newfound Neo-Cubism . . . I even gave Hockney bathing trunks (barely) . . .'

Hockney's many arms are firmly bound to his side. He is tied by the limitations of his art. Though he shares aims with Picasso, Braque, and Hockney, Kitaj is not a Neo-Cubist. His paintings demonstrates the ultimate failure of Cubism to resolve its spatial context. He doesn't rely on a distortion of perspective; he doesn't attempt to physically force an extra dimension into the canvas. He simply places the contrasting thoughts, references, and experiences on one canvas."

The School of London: the resurgence of contemporary

painting

by Alistair Hicks

Phaidon Press Limited, Oxford, 1989